|

Discover the basics of healthy nutrition and tips on making it part of your lifestyle. Healthy eating, or good nutrition, is simply eating adequate, well-balanced meals to support your body’s needs (World Health Organisation, 2018). At the heart of healthy eating is doing what helps you feel well. A healthy diet does not have to look a particular way and can accommodate many types of palates, dietary restrictions, and lifestyles. What matters is figuring out what foods help you feel like your best self. Healthy eating can protect you from malnutrition, which is a serious condition that occurs when your body is not getting the nutrients it needs. Many diseases, such as diabetes, cancer, and heart disease, are linked to poor nutrition (World Health Organization, 2022) while healthy eating can help promote both physical and mental wellness. Here are some more benefits of healthy eating:Longevity (or living until old age)Is positively associated with good nutrition, especially diets high in vitamins and minerals (Ahlberg, 2021). People who eat healthily are less likely to suffer from certain diseases which can cause long-term health issues or premature death, such as heart disease. Researchers found that longevity is not associated with specific “fad” diets, such as those that limit all carbohydrates or all fats (Lim, 2018). Rather, following a few basic nutrition principles can help people live longer, healthier lives. Lower risk of heart disease, cancer, and diabetesIs associated with eating a healthy diet (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2022). If you are worried about a family history of diabetes or heart disease, or simply want to lower your risk of suffering from illness, you might benefit from speaking to your physician about incorporating healthy eating into your lifestyle. Healthy Immune FunctionMeans the ability to fight everyday viruses and bacteria which cause disease. You may have started to pay greater attention to your immunity during the pandemic, and the good news is that it is possible to help your immune system function better through healthy eating. As we age, our bodies inevitably slow down, and immune function decreases, which is why older people are more susceptible to serious complications from diseases like the flu. Eating a diet rich in vitamins, minerals, and antioxidants, such as one that has plenty of fruits and vegetables, can help our bodies fight disease (Calder, 2022). HealthierPregnanciesWhich reduce the risk of both mothers and babies facing difficult complications or diseases, are strongly correlated with healthy diets (National Institutes of Health, 2022). Eating a healthy diet during pregnancy can promote brain development and healthy birth weight for babies, while simultaneously reducing risks to the mother, such as anemia (iron deficiency), fatigue, and morning sickness (Allen, 2000). Strong BonesAre a major part of wellness. This is true of children, whose bones are still growing, and adults, who can enjoy activities of daily life more easily when they don’t suffer from painful joints or conditions such as osteoporosis. A healthy diet is a major contributor to strong bones (Abrams, 2021). Improved Mental HealthHas been linked to eating a healthy diet in many research studies. New research suggests that while we don’t fully understand all the ways in which a healthy diet promotes better mental health, we do know that there is a strong association between poor nutrition and disorders such as anxiety and depression (Adan et al., 2019). On the flip side, improving your diet can benefit your mental health (Adan et al., 2019). Here are some healthy habits to get you started:Eat Lots of Fruits and VegetablesFruits, vegetables, and other plant-based foods, such as mushrooms or herbs, are excellent sources of vitamins, minerals, dietary fiber, plant protein, and antioxidants. Eating five or more portions a day is excellent for your overall health and can help prevent many diseases (World Health Organisation, 2022). Eat Protein EverydayProtein helps to build and maintain your bones and muscles. Some foods rich in protein are legumes, nuts, seeds, tofu, fish, eggs, chicken, beef, milk, yogurt, and cheese. If you eat seafood, consider having it at least twice a week because it provides many rich vitamins and healthy fats along with protein. Don't Skip BreakfastWhile you might be tempted to skip breakfast because you feel rushed in the morning, aren’t hungry right after you wake up, or think it might help you lose weight, recent research shows that people who skip breakfast as a habit are more likely to miss out on important nutrients and have more health problems than those who make time to eat a well-balanced meal to start their day (Fanelli et al., 2021). Add Fermented Foods to Your DietFermented foods, like kimchi, sauerkraut, or yogurt with live active cultures are not only delicious additions to your plate, they’re full of probiotics, which keep your gut healthy and happy. Probiotics, or friendly bacteria, have a whole range of health benefits, including better digestion, improved immunity, good skin and hair, and once again, improved mental health (Marco et al., 2017). In SumHealthy eating might seem daunting at first. But if you make small changes and lead from a place of treating yourself to the health and wellness you deserve, you might find yourself thriving and even enjoying the process. You might even choose to meet with a nutritionist or borrow a healthy cookbook from your library. Remember: even if those options are not available to you right now, it’s okay—a few simple tips can put you on the road to a healthier you. References

Discover tips for managing time, disconnecting from work, and caring for yourself. While work-life balance is something almost everyone knows about, very few people know exactly what it entails. To put it in simple terms, work-life balance is the amount of time you spend doing your job versus the amount of time that you spend at home – home time is, for example, time spent with friends, family, and pursuing your personal interests (Cambridge Dictionary, n.d.). Since the pandemic, the term ‘work-life balance’ has been under increased scrutiny due to its suggestion that our work and our personal lives are in different and adversarial spheres competing for our time. This can result in an unhealthy relationship with our work or personal life where we end up feeling guilty no matter which one we prioritize (Hochwarter et al., 2007). Some people believe in advocating for work-life integration versus work-life balance. They believe that a synergistic blending of our work and personal responsibilities is the best approach (Burke, 2006). This perspective places work as another spoke on the wheel of our lives, to be considered alongside other ‘spokes’ such as our family lives and personal well-being. Supporters of this approach argue that each element feeds into one another and is essential for us to thrive. Ultimately, whether you agree with work-life integration or work-life balance, overall the goal is to manage your time between work and home in a way that benefits you. When your work-life balance is off-center, there can be a myriad of mental, physical, and emotional problems that arise. For example, when you work long hours, it can lead to serious health issues such as (Sultan & Nag, 2020):

It can be tough though because many people believe that working a lot equates to being a good worker. However, working long hours isn’t the key to increased productivity. A study in 2015 found that when workers hit a certain number of hours, their productivity also decreased (Pencavel, 2015). At this threshold, their potential for mistakes and injuries also increased. In general, achieving a work-life balance is best not just for your well-being but also for your productivity. Here are some benefits of a better work-life balance:Increased JoyWe are happier when we have time for the people and things we care about. Increased ProductivityWhen you have time to rest and accomplish things personally, you are more likely to have a productive career. Better Care SatisfactionWhen you are not always stressed about reaching deadlines and thinking about work 24/7, you are more likely to be satisfied with your work. Better HealthWhen you achieve a work-life balance, it can help reduce stress. This leaves you more time for healthier activities such as exercise or mindfulness meditation. Tips for Work-Life BalanceHere are some tips to help with work-life balance (Bartlett et al., 2021): Time ManagementThe most important of the tips is learning how to best use your time. There are many ways to do this; You could keep a schedule and write down all the meetings or commitments you have for the week. This will enable you to organize your tasks more efficiently. Prioritize and Set GoalsOnce you have your schedule, you can prioritize your personal values and reassess your strategy to honor them. Ask yourself, what really matters to me, and am I doing it? Where am I making compromises, and should I? What are my alternatives? You may want to rethink what your values are and change what you prioritize. You may have different things you want to accomplish by the end of the day, the week, or even the year. Once you know your priorities, you can establish personal goals based on them to act as a guide in navigating your decisions. Put Yourself FirstSometimes, you have to advocate for yourself. To have better health, it may help to ensure you have time to exercise, plan your meals, and in general to have downtime for yourself. Another essential skill is learning that it’s okay to say no sometimes. Be careful not to overschedule yourself and spread yourself too thin—in the end, this can negatively affect your mental and physical health and your performance at work Develop a Support SystemThere is no shame in seeking support. We are fundamentally social beings, and building connections with our community is essential to a happy life. At work, it may help to join forces with co-workers that you know will support you and vice versa. At home, friends and loved ones may be able to help you with tasks such as childcare or household chores whenever you are overwhelmed at work. Making such bonds can help you when you are stretched for time. Know When to Seek Professional HelpLife inherently can be chaotic, and trying to manage it while also dealing with work stressors can become too much for anyone. If you feel anxious or depressed due to a disrupted work-life balance, feel no shame in seeking a mental health provider. In SumRemember that a work-life balance will not look the same for everyone. In fact, it could even be said that the perfect work-life balance doesn’t exist. Instead, a work-life balance is a continuous process. It may be helpful to examine your priorities and make changes accordingly periodically. References

Discover what makes something a need and how to know if yours are met. A need can be defined as a “physiological or psychological requirement for the well-being of an organism” (Merriam-Webster, n.d.). In other words, a need is something that you won’t be okay without. This can range from food and water to human contact and socialization. Our needs can also differ depending on the situation. In general, we have needs such as food because without it we can die. However, communication can also be a need since, without it, relationships can deteriorate. Basic needs, or primary needs, are the most essential. These include:

Maslow's Hierarchy of NeedsIn 1943, psychologist Abraham Maslow first introduced his concept of a hierarchy of needs (Maslow, 2012). Through this, he suggested that people are motivated to fulfill basic needs before moving on to more advanced ones. He was a humanist and believed that people have an ultimate desire to reach self-actualization, or in other words to be all they can be. However, to achieve this, the lower-level needs were required to be fulfilled first. There are five levels of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs that increase in complexity: Physiological NeedsThese include needs such as food, water, and clothing. These are also referred to as basic or primary needs. Safety NeedsWe need to feel safe and secure in our environment. This can include financial well-being and health security. Social NeedsThis includes the need to be loved and to love. Belonging to a group of both friends and family is important to our psyche. Social needs are psychological needs. Esteem NeedsThis is the need to be recognized by others for our accomplishments. Esteem needs are also considered to be psychological needs. Self-Actualization NeedsThis is the need to actualize our talents and skills. This includes obtaining the full use and exploitation of our talents, capabilities, and potentialities. People who achieve self-actualization are said to be fulfilling themselves and doing the best that they are capable of. According to this model, we can only obtain higher-level needs once we satisfy the lower level needs. For example, we can only begin to meet our needs for safety once we have secured our physiological needs. One method to analyze these questions is through a needs assessment. Here is a brief rundown on how to do one (Royse et al., 2009). Identify the PossibilitiesThis first step is about discovering all the possible personal needs you may have. Write down things in your life that bring you joy and make you feel successful or unsuccessful, and then identify the related experiences. Then with this, try to identify the patterns of behavior that created these experiences. Refine and Shorten Your ListNow that you have a list, let’s narrow it down to include only your most important personal needs. Identify the top ten experiences that appear most often then consider which of these include actual needs (again, your must-haves, requirements, essentials). Then from that list, select the top four personal needs that are most important to you from those experiences. Create and Execute a PlanFrom the previous steps you now have at least four personal needs. Make a list of activities/actions that will help you meet these needs, including the things you do every day as well as other extracurricular activities. For instance, if a personal need for you is to learn a new skill you may want to plan to go to a cooking class. Or perhaps if your personal need is creativity, you may take steps to start writing a new book or invest in painting. Whatever your need is, it could help to take initiative to plan and execute ways to fulfill that need. Tips for Meeting Your NeedsAfter identifying your needs, it may help to try and meet them to feel fulfilled. If you ignore your needs, it can become detrimental to your physical and mental health. Here are some tips to help meet your needs:

In SumNeeds are a natural and essential part of life. What is important is being able to differentiate between what we want and what we need and then being able to prioritize our needs. References

Discover how wish lists work and how to use this tool to advance your goals. Maybe you made wish lists when you were a kid and daydreamed about birthday and holiday gifts. Maybe you wanted to make sure that your parents picked out the right color clothes or the right version of a video game. As adults, our birthday wish lists might evolve into Pinterest boards, bucket lists, wedding registries, and lists of goals and New Year’s Resolutions. Wish lists can be a valuable tool for anyone of any age to identify and work toward meaningful goals. A wish list is a tool to keep track of what you want. These lists are often organized by theme–potential travel destinations, hair care products, and what you’re looking for in your next apartment. Wish lists can be fun, serious, private, shared, organized, messy, detailed, vague, practical, and/or fanciful. You can keep a wish list in many formats–in a notebook, on an app, or as a collage. The list acts as a repository for and reminder of your wants. For instance, it can remind you to request a certain amount of vacation time when negotiating a job offer. The list can also keep wishes (or goals) at the forefront of your mind so you’re motivated to keep working toward them–if you remember that trip to Italy you want to take, you might be inspired to figure out a better savings plan or to ask for a much-deserved raise. Wish lists could be a step toward creating clear written life goals. Writing down goals may help you achieve them (Matthews, 2007). Wishes, of course, aren’t quite the same as goals and can be as pie-in-the-sky as you want. Still, bringing wishes into written, spoken, or visual awareness seems like a prerequisite to making them real. After all, what is a goal but a wish with a plan and intention? Ideas for Your Wish ListWish List for Your Next RelationshipSimilarly to a job wish list, a relationship wish list can remind you what you deserve and what matters to you when searching for romantic partners. Instead of looking for someone of a specific height or hair color, or someone who shares all your specific interests, try listing qualities like, “is attractive to me,” or, “someone I enjoy spending time with and feel intellectually stimulated by.” This strategy may help you avoid settling for less than you deserve while opening the search up to potentially great partners you may never have considered otherwise (Ury, 2022). Books to ReadYou could make a goodreads.com account for this list. It can help you keep track of new books you want to check out from the library; you can even set a reading goal for the year. If pen and paper are more your speed, a basic notebook or a reading journal work just as well. Movies to WatchSimilarly, letterboxd.com is a good place to keep a watchlist of movies so you’re not stumped the next time a friend says, “So…what do you want to watch?” Basic accounts on both websites are free. Wish List to Curb Impulse SpendingGroening et al. (2021) argue that keeping wish lists (especially private ones) might prevent purchasing items by allowing shoppers to “cool off” their excitement about the item or by making them feel that they own the item already (and so, don’t need to buy it). Adding an item to a wish list also introduces an additional decision point (to place the item on the list or not, and to buy it or not), which gives you extra opportunity to rationally consider whether the purchase is a good idea (Popovich & Hamilton, 2014). Reverse Wish ListJust as you can make a list of what you want and need, you can make a list of deal breakers. It’s important to articulate what we will and will not tolerate–in other words, to set boundaries. For example, if you just got out of a troubled relationship, you can write down all the features you won’t accept in a new relationship. Gift-Giving Wish ListYou can keep wish lists for others as well as yourself. For example, if a friend says they want something, it’s a good idea to write down their birthday somewhere you can find it. How to Make a Wish ListWhen making a wish list, you don’t have to be practical or realistic–you can write down anything you want. You can try the strategy of setting a timer for 5-10 minutes and writing down everything that comes to mind, without self-censoring. A wish list is a great place to dream big. There’ll be plenty of time to edit and rank items later if you want to. When you review the list, you can amend anything that seems too out there. If something on the list seems out of reach at the moment, you can leave it on the list as a longer-term goal while acknowledging that a more modest goal is more attainable right now. A second draft is also a good time to do research. If you’re making a wish list for a car, for example, you can read online reviews and search available models. In SumWish lists aren’t just for kids–they can be a powerful tool for people of all ages to clarify and remember their goals and desires. Wish lists can allow us to exercise our imaginations, expand our ideas about what we deserve and what is possible for us, and begin turning our half-conscious desires into active goals and real achievements. Making a wish list can also be an act of hope and an investment in a brighter future. Given the uncertainty of the modern world, many of us could use a little wish list whimsy. References

Learn more about relaxation and techniques for slowing down. In American culture, relaxation is considered a luxury, something only those privileged enough to have sufficient resources get to enjoy. However, relaxation is actually an important contributor to our mental and physical health. When we don’t allow ourselves to take time to unwind, the harmful effects of daily stressors begin to accumulate and can contribute to psychological and physical maladies like depression, memory loss, heart disease, stroke, and diabetes (just to name a few). Relaxing gives our bodies and minds a chance to recover from stress and live our best lives. Physiologically, relaxation is the activation of our parasympathetic nervous system. This activation slows our heart rate, lowers our blood pressure, reduces muscle tone, slows our breathing, and prepares our bodies for rest and rejuvenation. Luckily, there are a number of ways we can activate our parasympathetic nervous systems and help our bodies recover from the damages of our stressful lives. Here are a few examples: Progressive Muscle RelaxationProgressive Muscle Relaxation (PMR) is a technique that helps us learn what it feels like when our muscles are tense versus when they are relaxed so that we can notice the tension when we are stressed out and willfully release it (Cawthorn & Mackereth, 2010). In general, the steps to PMR are the following:

MeditationMeditation has been used as a relaxation tool for centuries and the current body of research supporting the positive benefits of meditation is immense. Some of the observed effects of meditation include slower heart rate, muscle relaxation, increased cerebral blood flow, increased production of melatonin, and greater activation of brain regions associated with non-verbal, intuitive, and spatial processing (Perez-De-Albeniz & Holmes, 2000). There are many kinds of meditation and different people will benefit differently from each, so it might be helpful to try out more than one kind to see what works best for you. MassageMassage is often viewed as a particularly indulgent luxury, but studies show it’s a highly effective therapeutic technique. For example, massage has been associated with reductions in pain and anxiety, and improvements in mood, relaxation, and sleep in patient populations (Dreyer et al., 2015; Jane et al., 2011). There are many forms of massage therapy, and each form is suited for different needs. For example, if your goal is simply relaxation, a Swedish massage might be best for you. Whereas if you are in need of pain relief, a deep-tissue massage could be the way to go. Before scheduling a massage session, it might be helpful to check out what your options are and discuss what type of massage will best meet your needs with your massage therapist. YogaYoga is another highly effective relaxation technique that has been in practice for centuries (De Benedittis, 2015). Yoga is sometimes used as exercise, but it doesn’t necessarily have to be. Often, yoga functions more as a moving meditation, giving your mind a specific focus to help quiet the internal chatter as you become absorbed in synchronizing your movements with your breath. Research has shown that yoga can help reduce pulse rate, and blood pressure, both of which are important physiological changes for relaxation (Jain et al., 2010). Yoga has also been shown to reduce other physiological symptoms of stress such as inflammation and the production of stress hormones (Ross & Thomas, 2010). Music and SoundsListening to music is also well-documented as a helpful therapeutic technique for reducing stress. For example, listening to music has been shown to affect aspects of your physiology such as lowering your heart rate, reducing blood pressure, and limiting stress hormone levels (de Witte et al., 2022). The neural mechanisms by which music improves mood, relaxation, and well-being are not well understood. One possibility involves the synchronization of our bodies and our brain activity with musical qualities such as rhythm and tempo (Kim et al., 2018). For example, you’ve probably noticed yourself involuntarily tapping your foot to the beat when listening to a song. This phenomenon is known as “entrainment” and is essentially the rhythm of the music influencing the rhythmic activity within your motor system. In SumIn today’s fast-paced and often stressful world, taking time to relax is more important than ever. Without allowing our parasympathetic nervous system to take over for a little bit and give our bodies a break from the damaging effects of prolonged stress, we can end up exhausted, depressed, and even physically ill. There are many effective techniques for unwinding and reducing stress that can be simple to incorporate into our daily lives. Regardless of the relaxation method you choose, it is important to use it regularly, especially if you have many stressors in your life. References

Learning how to heal ourselves can bring us back to a state of well-being. We likely all struggle with the remnants of past emotional or physical challenges. So we probably would all benefit from some self-healing. However, self-healing may offer greater benefits for those who are feeling highly self-motivated to engage in the self-healing process—that is, to take the time to implement self-healing techniques and activities in their lives. Just as it takes time to build a new skill, self-healing can take time and effort. So effort here is key to seeing results. Self-Healing TechniquesThe following self-healing techniques can benefit both your emotional and physical health. They may help you feel a bit better immediately but their real power emerges when you practice them regularly. Regular practice can result in long-term changes in your brain that can contribute to happiness, resilience, and well-being. Try Self-CompassionOftentimes, we’re harder on ourselves than we are on anyone else. We might even get mad at ourselves for being sick or unable to get over past hurt or rejection. But by being extra hard on ourselves, we do ourselves no good. Instead, we just make it harder for our body and mind to heal. That’s why self-compassion can be a great tool for self-healing. We might start by writing ourselves a self-compassionate letter—a letter where we say kind things to ourselves and write about how we will support ourselves moving forward. Related to this, we might also set better boundaries to keep others from crossing the line with us. Or, we might develop assertive communication skills so that we can advocate for our needs and take better care of ourselves. Get More SleepDid you know that we do much of our healing while we’re asleep? That’s right—lack of sleep can weaken the immune system making it harder for the body to heal itself (Ibarra-Coronado et al., 2015.) Lack of sleep can also contribute to higher levels of stress hormones like norepinephrine and epinephrine (Zhang et al., 2011). These hormones can lead us to feel more anxious and burned out. That makes sleep absolutely essential for self-healing. Too often, we stay up late, get up early, and force ourselves to stay awake when we’re exhausted. We might prioritize getting extra work done or going to the gym instead of sleep. But if we desire to heal ourselves, this is likely not the best move. Extra work and exercise just give our bodies a longer to-do list and if we’re not properly rested, we may just be hurting our bodies even further. Breath DeeperIf we’ve been struggling with stress, trauma, or physical health issues, our sympathetic, “fight-or-flight” system has likely been activated for a while. To calm our sympathetic response, we need to activate the parasympathetic nervous system, which is largely responsible for calming down our fight or flight response and helping us return to a less stressed state. One of the easiest ways to activate the parasympathetic nervous system is with controlled and deep breathing. For example, SKY breathing—a technique involving cycling slow breathing (2-4 breaths per minute) then fast (30 breaths per minute), then three long “Om”s, or a long vibrating exhale—has been shown to lower anxiety (Zope & Zope, 2013). Another popular breathing technique is “box breathing”. This involves breathing for a count of four, holding for a count of four, exhaling for a count of four, and holding for a count of four. Practice breathing this way for a little bit each day to help boost parasympathetic activity and help your body recover from past challenges. Try Mindfulness MeditationMindfulness is a technique that involves “paying attention on purpose, in the present moment, and non-judgmentally to the unfolding of experience moment by moment” (Kabat‐Zinn, 2003). Research shows that mindfulness interventions can help reduce both anxiety and depression (Khoury et al., 2013). Self-Healing ActivitiesHere are a few other activities that you might find to be helpful for self-healing. Try Positive VisualizationVisualizing yourself in a relaxing, positive space can help soothe your body and ease your mind. Listen to Soothing MusicCalming music can help reduce stress and set the scene for greater self-healing. Cut Out Unhealthy FoodsUnhealthy foods like hydrogenated oils, sugar, and caffeine put extra stress on your body and may prevent healing of all sorts. Start a Gratitude JournalPracticing gratitude is a great way to bring more positive emotions into your life. These positive emotions can help counteract the negative emotions that prevent healing. Try GardeningResearch suggests that gardening has multiple benefits for our well-being and can even help us reduce depression. In SumWe all have challenges that we need to heal from. Some of us have emotional challenges, others of us have physical challenges, and some of us have both. Luckily, we actually have a lot of power to make positive changes to our well-being. We can shift the way we think and how we treat our bodies. As a result of these efforts, we can begin to heal and recover from the hardships we’ve experienced. References

Examples of proactivity and tips for being more proactive. Proactivity is defined as the act of intentionally looking for ways to change one’s environment, rather than waiting to be forced to act (Bateman & Crant, 1993). Being proactive means seeing one’s environment as something that can change, and seeing oneself as a person who can change that environment. And importantly, proactivity is something that comes from within us, from an internal source of motivation or inspiration. The clearest benefit of being proactive is that proactive people experience more success in their professional and personal lives (Fuller & Marler, 2009). This may be because proactivity leads to getting one’s needs met. The satisfaction that comes with this not only makes us feel better about ourselves, but also increases our interest in continuing to be proactive. In other words, over time a person can become more automatically proactive through building a positive feedback loop between proactive behaviors and positive emotions and thoughts about oneself (Strauss & Parker, 2014). Perhaps it is no wonder, then, that people who are proactive show higher levels of healthy independence, feel more vital and confident, and see themselves as competent and able to determine their own fates (Cangiano & Parker, 2015). It is likely that these personality traits and proactivity positively reinforce each other, too. What Leads to Proactivity?As we saw above, proactive behaviors lead to more proactivity because they generally get positive, desired results. But certain personality traits seem to be associated with being more proactive, too. For example, people who are more proactive are generally more extroverted, more open to experience, more conscientious, and less neurotic (Fuller & Marler, 2009; Wanberg & Kammeyer-Mueller, 2000). People who take an active interest in learning and see themselves as capable in their career also tend to be more proactive (Fuller & Marler, 2009). It also appears that people who actively seek feedback about their own behavior, and who seek to build connections with others, are more proactive (Wanberg & Kammeyer-Mueller, 2000). Seeing as these tend to be proactive behaviors in and of themselves, this makes a lot of sense. Tips on ProactivityBy now, you might be saying, “okay, I get it, proactivity is good. But how do I become more proactive?” Plan AheadOne way is to find and use tools of planning ahead (Presbitero, 2015). This is particularly effective for career success, as people who plan for their careers are more likely to take proactive steps toward their career goals (Presbitero, 2015). Some examples of planning ahead in a career context can include researching career trajectories online, seeking out informational interviews with people in your field, and using goal-setting apps or planners to build a vision for yourself. Change your MindsetMore generally, you might be able to increase your proactivity by changing your mindset about the different environments you inhabit. For example, we can make a deliberate effort to see ourselves as leaders in our homes, schools, and workplaces (do Nascimento et al., 2018). We can ask ourselves, “How would somebody who is responsible for everything here look at this room? This project proposal? What would they say?” It can be helpful in this context to articulate what your own values are, too, because these can also be a lens for seeing the world that motivates proactive behaviors (do Nascimento et al., 2018). Develop a Critical EyeFinally, you can walk through the world with a loving and critical eye. What do I mean by this? Look around the room you’re sitting in. If you were somebody who wanted the very best for this room, what would you change? Would you clean the windowsills or buy new screens? Redo the paint in the corner? Add a piece of artwork to an empty stretch of wall? If this sounds like a lot of effort, we get it – it is more effort. But it will sustain itself and you: people who are proactive are more connected to their reasons for working and caring, and that motivates them to keep helping others (Lebel & Patil, 2018). In SumIf you are reading this article, you probably aspire to be more proactive. We encourage you to start in a place where you are already passionate. Whether you want more intimacy in your romantic relationship, more cohesion in your team at work, or more time to spend on a beloved hobby, you can ask yourself: what things are in my power to change? What might be in my power to change that I’ve been ignoring or denying? Where do I stand to make the most change? You and the people around you will all be grateful for the effort you proactively put in to improve the world. References

Explore the meaning of adaptability and how to cultivate it within yourself. The Greek philosopher Heraclitus famously said, “Change is the only constant in life.” Try as we might, it is impossible to predict the curveballs that life throws at us. Maybe your job is implementing a new software system and you need to learn how to use it, even though you have no experience with this technology. Maybe a hurricane hits your state and you have to live without power and water for a while. Both examples represent unexpected changes in your environment that you must respond to. Approaching these situations with an open mind and a flexible approach will yield more positive results than approaching them with a rigid, closed state of mind. Adaptability is the skill of molding your actions and reactions to the changing environment around you. Specifically, it is “the capacity to make appropriate cognitive, behavioral, or affective adjustments in the presence of uncertain or novel circumstances” (VandenBos, 2007). Being adaptable means, you are flexible in your thinking and behaviors when the circumstances around you are changing. What sort of changes might require adaptation? It could look like anything from an unexpected traffic jam that makes you late for an important presentation to a tornado that causes property damage. In each of these situations, you are unable to change your environment, but you can adjust your reaction. Being thoughtful and considering multiple solutions will likely lead to good results. Freezing up or being angry at the situation won’t change much at all. Since change is a constant of life, adaptability is a skill that allows you to effectively adjust to that change. When you think rigidly, you may miss out on opportunities for better solutions because you refuse to consider any ideas other than your own. This might push others away as they feel you don’t hear or appreciate their thoughts and ideas. Getting other people's opinions on how to approach an obstacle in your life may yield a solution that you never thought of before and improve your interpersonal communication and relationships. The ability to be flexible in your thinking is called cognitive flexibility–a component of adaptability. Multiple benefits for people who demonstrate cognitive flexibility have been identified. Benefits of Cognitive Flexibility

Are You Adaptable?Answer the following questions with “yes” or “no” to see if you have adaptability or determine if it is a skill that you might need to work on some more.

How to be More AdaptableSince change is one of the only constants in the world, adaptability is a skill that can help you weather the storm. Some people may find adaptation easy while others might find it more difficult. If you would like to develop this skill within yourself, consider building the following strengths. Build Up Your Self-ConfidenceSome people may not be very adaptable because they don’t believe in their abilities. Working on developing a greater sense of self-confidence can help you recognize that you are capable of adapting to new situations. See a Different PerspectiveLooking at life from another point of view can help you realize there are many ways to solve the same problem. Consider a situation in your life that you need to adapt to and then approach that situation from someone else’s point of view. It may help you see new solutions. Recognize that Failure HappensAll of your attempts to adapt may not work right away and that’s okay. Be persistent and keep working through life’s challenges until you find a solution. Failures can serve as invaluable lessons on the path to success. In SumAdaptability is a skill that you can use to respond to the ever-changing world more effectively around you. Being flexible and adaptable in your thoughts can help you see things from a different perspective which may yield better solutions to your problems. To help build adaptability, build up your self-confidence, look at your problem from a different perspective, and recognize that failure is okay. Trial and error are a natural part of the adaptation process. Even if new adaptations don’t work right away, keep at it until you find an angle that works. References

Learn how we define trust issues, recognize them, and work to improve them. Trust is believing that it is safe to be vulnerable with somebody else because they are willing and able to respond to you in a way that will meet your needs, or at least not harm you. The amount you trust another person comes down to how confident you are that they will respond that way. The more confidence you have, the more consistently you believe they will meet your needs or even respond with the same level of vulnerability and trust that you showed them. Having trust issues means suspecting that another person does not have the ability or the integrity to meet your needs in a situation (Covey, 2006). Somebody with trust issues does not believe it is safe to act on the actions, words, and decisions of another person; in fact, people with trust issues often think that the other person is acting in ways that will deliberately harm them (Lewicki & Weithoff, 2000). Social scientists have studied closely how consistent trust issues are for people. They have found that while our levels of trust vary a lot from one situation to the next, most people have a range of trust that they show others (Fleeson & Leicht, 2006; Weiss et al., 2021). In other words, most everybody trusts a close friend more than an acquaintance or a stranger, but some people will trust their close friends more than other people will. Our perceptions of the trustworthiness of other people are important determinants of how trusting we are in each situation (Weiss et al., 2021). What are some symptoms of having trust issues? First of all, we know that people who are regularly jealous of others have lower levels of trust (Guerrero et al., 2014). For example, somebody who gets jealous when they see their romantic partner talking to somebody else probably does not trust their partner to be faithful. Second, we know that people who see others as threatening, lacking integrity, or generally incompetent will be less likely to trust other people (Mayer et al., 1995).This finding makes a lot of intuitive sense – if you thought other people were going to mess things up or hurt you, even if it was unintentional, how much would you trust them? So people who make frequent statements that indicate they believe others are dishonest or unable to do their jobs may be experiencing trust issues. Like so many relationship issues, trust issues are usually thought of as resulting from insecure patterns of attachment (Cassidy & Shaver, 2008). We form insecure patterns of attachment when we don’t consistently get the love and support we need from caregivers as children. Perhaps a parent promises special time with a child and rarely delivers on the promise, or only sometimes comforts the child when they are clearly very upset. When this happens again and again over time, we develop a “working model” of relating to others that tells us not to trust others with our needs and desires (Bowlby, 1982). We are constantly changing our ability to trust others. Sadly, this means that people who experience huge, painful breaches of trust in adulthood, even if their early relationships were solid, can develop trust issues. Indeed, many adults who have trouble keeping a romantic relationship going report that broken trust in past relationships is a big reason why (Peel & Caltabiano, 2021). At the same time, it also means that people who had few trustworthy relationships in childhood can work on and heal from their trust issues in adulthood. How to Improve Trust IssuesOne way to improve one’s trust issues is to cultivate the sensations that are opposite to what we feel and experience when we are distrustful. In place of the negativity, uncertainty, and closed-off way of approaching the world that come with trust issues, we can seek to build openness, positivity, and confidence in our conflict management skills (Suwinyattichaiporn et al., 2017). What might this look like? It could involve activities that help one intentionally focus on instances when trust has been rewarded. Identifying positive instances of trust throughout one’s day could help: from the other drivers who stayed in their lanes during one’s commute to the family member who calls regularly to say hi, people are being consistent and trustworthy more often than we might give them credit for. In relationships where trust has been broken, we can also learn how to seek greater trust. If there are people in our lives who have withdrawn from us or let us down, we can find new ways – often, softer and gentler ways – to state our needs, describe how meaningful it would be to have the other person meet them, and hope for the best (Burgess Moser et al., 2015). In SumTrust issues happen for almost all of us somewhere in our lives. That’s natural and good. If you can find somebody who’s never been betrayed or hurt or let down, don’t be jealous. That person has never had to figure out who is trustworthy and who isn’t, and how to make sure their trust is better returned next time. We are all constantly in this process of figuring out where and when we can be vulnerable. If trusting others has been hard for you, remember how common this is and that you probably are this way for very good reason: somewhere along your life’s journey, there’s been at least one relationship that taught you not to trust. That’s not your fault. Hopefully, you now feel a little more empowered to take action to help yourself, or somebody else, with trust issues. References

Get the lowdown on the science behind moods. Scientists define a mood as a prolonged period of time in which you tend to feel certain feelings and have thoughts that mirror those feelings (Watson & Clark, 1997). For example, when you are in a negative mood, you might feel worried or upset, and thoughts will generally follow this pattern, too. Moods have two chief characteristics: whether they are positive or negative, and how intense they are (Watson & Clark, 1997). When you say you’re in a relaxed mood, for example, you are probably feeling positive, but in a mild way. By contrast, when you are in an angry mood, things probably feel intensely unpleasant. We are usually aware to some degree of the nature of our mood, even if we can’t change or control it (Watson & Clark, 1997). You probably can often sense when you’re in a good mood or a bad mood. One of the things that distinguishes moods from emotions is that moods are longer-lasting. Once you’re in a particular mood, it will likely continue for some time, even though it may not seem related to anything in your current environment (Russell, 2003). Scientists think that moods are created by the experiences we have, especially experiences happening close together in time (Nettle & Bateson, 2012). For example, a morning of inconveniences – a traffic accident snarling traffic, a long wait at the doctor’s office, and then a bumped-up deadline at work – could put you in a state of anxiety. If you’ve ever had a morning like this, your response was actually adaptive: you reacted to an environment full of unexpected threats by putting your system on high alert so that you would be better able to respond to the next threat. Psychologists think moods are important to study, not just because they’re a very important part of the lived human experience, but also because they impact how we perceive and respond to the world (Nettle & Bateson, 2012). You could call this emotional thinking – a phenomenon where our feelings shape the very possibilities of our thoughts. Mood TypesAs noted above, moods can be characterized by two dimensions: how pleasant or unpleasant they are, and how intense they are. Another way to think of this is how focused on reward versus threat we are (Nettle & Bateson, 2012). From this understanding, we can identify four examples of moods: Mildly Unpleasant Moodhis includes states of boredom or irritation. You can think of boredom as the unpleasant absence of engaging activities, and irritation as a mood where your environment is repeatedly, but mildly, unpleasant to you. Strongly Unpleasant MoodThis includes states of anxiety and depression. In this context, your feelings more powerfully influence your thoughts, and it can be very difficult to feel positively about your experience of the world. Mildly Pleasant MoodA sense of relaxation is probably the best example here. People who are relaxed are not highly motivated to do anything, but they are feeling good. Strongly Pleasant MoodHappiness, contentment, and joy are examples of strongly pleasant moods. Not only are you feeling very good, but you’re probably more motivated to do things to maintain or amplify those feelings. It can be helpful for your own ability to skillfully respond to your moods to think about what each mood type is encouraging you to do. Our moods, like our emotions, attune us to our environments in specific ways. A positive or pleasant mood makes us more likely to pay attention to the rewarding things in our environment, while a negative or unpleasant mood makes it easier to notice things that are threatening or punishing (Carver, 2001). Research thus far suggests that mood trackers may be helpful for us to better understand how our moods change (Malhi et al., 2017). However, it will take more research before we know whether it is the mindfulness of one’s moods from hour to hour, or the insights gained from the process, that are most helpful. In SumAs with so many aspects of being a human, moods are something we handle best through acceptance. Our emotional reactions to the events of our lives are natural, and it’s just as natural that, over time, those reactions form the basis for a mood. While a mood may last for hours or even days, it is never permanent. Being aware of how our moods influence our thinking and decision-making can help us remain skillful and effective regardless of how we’re feeling. References

Learn more about tension and the role of stress in our experience of tension. Tension, as it relates to our psychological experiences, can be defined as a state that is associated with conflict, dissonance, instability, or uncertainty. Psychological tension also creates a desire for resolution and feelings of expectation, anticipation, or prediction concerning future events that are potentially emotionally impactful (Lehne & Koelsch, 2015). Tension is typically experienced in our bodies as tightness or stiffness in our muscles. This kind of tension can be quite painful and can sometimes severely restrict your ability to move. Tense muscles may be tender to the touch and feel like a chronic cramp or spasm. Tension is a characteristic present in a variety of physical and emotional experiences. Here are a few examples of where we might observe tension:

The Role of StressOur fears and anxieties don’t just occur in our minds, they are expressed throughout our bodies as well. When we are stressed, the branch of our nervous system called the sympathetic nervous system is activated. Activation of the sympathetic nervous system is the physiological component of our fight or flight response. That is, our sympathetic nervous system is responsible for preparing our bodies for action when we feel as though we are in danger. Part of this preparation is the release of a neurotransmitter, called acetylcholine, which is responsible for making our muscles contract. Thus, when we are stressed out, our bodies interpret that stress as danger and activate our sympathetic nervous system, which promotes the release of acetylcholine, and ultimately leads to the contraction of muscles, even when we don’t want it to. Research has shown that stress-induced muscle contractions, or muscle tension, are especially prominent in the face, neck, and shoulders (Bansevicius et al., 1997; Glaros et al., 2016). You might notice this effect if you clench your jaw or raise your shoulders when you are stressed. However, stress-induced muscle tension can occur throughout your body and isn’t necessarily localized to your head, neck, and shoulders. Tips to Reduce TensionBecause tension lives in our bodies, even when it’s born in our minds, the best way to reduce tension is through processes of physical relaxation. Anything that makes you feel relaxed could help, such as a walk with your dog, a conversation with a dear friend, or a cup of hot cocoa. In addition to the methods of relaxation that you know to be effective for you, there are multiple scientifically supported, non-pharmacological methods for achieving tension reduction through physical relaxation including Progressive Muscle Relaxation, yoga, heat therapy, cold therapy, and massage. Reduce Tension with Progressive Muscle RelaxationOne of the most common and most scientifically supported methods of tension reduction is a practice called Progressive Muscle Relaxation (PMR). Progressive Muscle Relaxation involves the conscious tightening and releasing of muscles throughout your body. Studies have shown that even a brief Progressive Muscle Relaxation intervention can help reduce psychological stress and tension (Dolbier & Rush, 2012). The process of Progressive Muscle Relaxation typically goes like this:

Reduce Tension with YogaReduce Tension with Heat TherapyHeat promotes increased blood flow, metabolism, and elasticity of connective tissue. Increased blood flow and metabolism are thought to help with pain relief by accelerating the breakdown of pain-inducing toxins in the muscles and the distribution of nutrients our muscles need to heal (Tepperman & Devlin, 1986). Increased elasticity improves range of motion and decreases the feeling of stiffness. It’s important to be cautious about using heat therapy if you have multiple sclerosis, poor circulation, spinal cord injuries, diabetes, and arthritis because heat can contribute to disease progression and increased inflammation or could cause burns (Malanga et al., 2015). If you are unsure if heat therapy may be right for you, talking with your doctor is always a good idea. Reduce Tension with Cold TherapyReduce Tension with Massage Therapy Massage involves the application of pressure to the soft muscle tissue which causes an involuntary relaxation response. The relaxation response decreases activation of the sympathetic nervous system which results in a reduction in blood pressure and stress hormones. In other words, it decreases the physical effects of stress. Massage also promotes blood flow, circulation of lymphatic fluid, and the release of deep connective tissues, which reduces painful contractions and spasms (Yates, 2004). In SumTension is a common experience that can range from uncomfortable to debilitating. It is important to remember that our emotions live in our bodies, so even when we manage to ease the pain of muscle tension, we are still prone to experiencing more episodes of tension if we don’t manage our stressors. Because tension seems to exacerbate stress, easing the physical effects of tension is an important step in managing our stress, but it isn’t the only course of action. Truly finding lasting relief requires tending to both our bodies and our minds. References

Discover the definition and function of serotonin and how to boost your serotonin levels. First, serotonin is a neurotransmitter, which means it is a chemical that moves back and forth in the space (called the synapse) between two nerve cells, or neurons. When one neuron is ready to send a message to another, it sends an electrical signal to its end, which causes a neurotransmitter such as serotonin to communicate that message to another cell. Once that message has been communicated, the neurotransmitter can stay with the new cell, return to the old cell, or hang out in the space between them. Certain neurons are programmed to interact with certain neurotransmitters, and neurons that communicate with other cells via serotonin are found throughout your central nervous system – in other words, throughout your entire body (Fuller & Wong, 1990). Neurons that use serotonin are also found in especially high amounts in your gastrointestinal tract – what we commonly call the “gut” (Furness & Costa, 1982). Since the role of a neurotransmitter is to help neurons communicate with each other, having just the right amount of serotonin where it’s needed is key to the healthy functioning of any organism, including humans. Serotonin facilitates communication throughout our central nervous system, helping to regulate many different body functions. While you might already be aware that serotonin levels affect our mood and emotions, serotonin is also involved in the regulation of our sleep, memory, appetite, digestion, body temperature, and how awake and alert we are (Jacobs & Azmitia, 1992). Your body’s goal in regulating itself is to reach homeostasis, or a balanced, “just right” place for each body function. Serotonin plays a critical role in trying to find that balance, and when the balance isn’t there, problems result. If there is too little or too much serotonin reaching the part of the brain called the hypothalamus, for example, it may be harder to keep your body temperature regulated. And if serotonin levels are off in your hippocampus, you may focus too much or too little on certain negative emotions or thoughts (Yabut et al., 2019). Ways to Boost SerotoninSince our bodies cannot naturally produce tryptophan – the amino acid that is converted into serotonin – we rely on getting tryptophan from our food. The foods we eat impact how much serotonin is in our brains and where specifically it is found (Haleem & Mahmoud, 2021). Just as important, research tells us that eating foods high in tryptophan can improve our moods and decrease our anxiety (Lindseth et al., 2015). DairySince our bodies cannot naturally produce tryptophan – the amino acid that is converted into serotonin – we rely on getting tryptophan from our food. The foods we eat impact how much serotonin is in our brains and where specifically it is found (Haleem & Mahmoud, 2021). Just as important, research tells us that eating foods high in tryptophan can improve our moods and decrease our anxiety (Lindseth et al., 2015). MeatYou might have heard before – correctly – that turkey provides plenty of tryptophan. But chicken also contains high amounts of tryptophan, as do chicken eggs. FishYou can also get tryptophan from canned tuna, but you’ll get a huge boost from eating salmon. OatsIf you want to start your day off with a healthy dose of tryptophan, a bowl of oatmeal is an effective place to start. Nuts and Seeds Peanuts provide a good supply of tryptophan, as do walnuts and pumpkin seeds. Dark Green Leafy VegetablesKale and spinach are also good sources of tryptophan. SupplementsScientific research has shown that at least one serotonin supplement, 5-Hydroxytryptophan (5-HTP), has positive effects. In clinical trials, people who are given a pill containing 5-HTP have experienced less appetite, better sleep, and decreases in their anxiety and depression (Halford et al., 2011; Maffei, 2020). The more we learn about serotonin, the clearer its vital role in regulating our minds and bodies becomes. If you think you might be experiencing the symptoms of somebody with low serotonin levels, I encourage you to talk to your primary care physician. If you are curious about serotonin supplementation, know that the risks appear to be minimal, and the upsides are considerable References

Learn how this brain chemical works and why it’s important for your health. What is GABAGABA is the brain’s primary inhibitory neurotransmitter (Buzsaki et al., 2007). When GABA is released, it’s almost like pressing down on the brain’s brake pedals, slowing things down and limiting or preventing excessive neural activity. When GABA binds to a neuron, that neuron becomes less likely to generate an electrical impulse. The neuron then requires more contact with excitatory neurotransmitters to fire. This is a critically important job - too much brain activity can lead to several negative effects including seizures and convulsions. Some of these negative effects may irreparably damage brain cells, sometimes even leading to death. GABA deficits and excessive brain activity have been implicated in serious degenerative brain disorders like Huntington's, Parkinson's, and Alzheimer's diseases (Wong et al., 2003). Even when the effects of excessive brain activity aren’t deadly, they can still negatively impact health and well-being. For example, impaired GABA transmission and excessive brain activity may contribute to sleep disorders, depression, anxiety, ADHD, schizophrenia, and other mental health disorders. The inhibitory effects of GABA are necessary for a healthy, balanced, and well-functioning neural system. As the brain’s primary inhibitory neurotransmitter, GABA is critically important to neural activity across the brain and plays a role in several different mental and cognitive processes. In the parts of the brain responsible for decision-making and cognition, higher concentrations of GABA are associated with better cognitive functioning in older adults (Porges et al., 2017). In the part of the brain responsible for visual perception and information processing, more GABA predicts better performance on a visual decision-making task (Edden et al., 2012). Similarly, in the part of the brain responsible for the coordination of movement, higher levels of GABA are associated with better performance on a tactile decision-making task (Puts et al., 2011). These results suggest that GABA is critically important to the healthy functioning of many different parts of the brain. The Benefits of GABAImpaired GABA functioning may be partially reversed by pharmacological or dietary interventions that increase GABA (Ngo & Vo., 2019). Some of the specific beneficial effects of increasing GABA may include:

In SumIt may seem counterintuitive that a chemical that slows down brain activity can be so important to a healthy and well-functioning neural system. Without the inhibitory neurotransmitter GABA to prevent excessive neural activity, brain cells would fire excessively, leading to tremors, convulsions, seizures, and eventual cell death. Although less dramatic, excessive electrical activity in the brain may also result in insomnia, anxiety, depression, hypersensitivity, hyperactivity, and impaired cognitive functioning. The presence of GABA within the brain works to counteract some of these distressing effects of excessive neural excitability. A balance between excitation and inhibition of electrical impulses is key to a healthy neural system and GABA is one of the keys to this balance. References

Read on to learn about the theory and research surrounding quality of life and tips for improving yours. Do you have a good quality of life? What exactly does quality of life refer to? Does quality of life simply refer to happiness or is it more complicated than that? Quality of life is discussed in various fields of study, including psychology, international development, economics, and healthcare. The term can refer to different constructs depending on the context in which it is used. For this reason, and possibly frustratingly, there is no single widely agreed-upon definition of quality of life. Having said that, the World Health Organization (WHO) provides us with a sense of direction by presenting one definition. They define quality of life as “an individual's perception of their position in life in the context of the culture and value systems in which they live and in relation to their goals, expectations, standards, and concerns” (who.int, n.d.). Because of the WHO’s international influence, their definition is significant—especially since it is used in much public and global health research. An important takeaway from their definition is that quality of life is a subjective measure of one’s well-being. Of course, even this key point is debated, with some researchers insisting that quality of life must involve objective as well as subjective measures (Karimi & Brazier, 2016). While there are numerous ways of thinking about quality of life, for this article, we will focus predominantly on how the concept is relevant to you and your well-being. To this end, we will focus mostly on subjective measures, as well as health-related quality of life (HRQoL), which excludes non-healthy aspects of quality of life, such as economic and political circumstances. The main reason for this is that you likely have more control over your health-related quality of life (both physical and mental) than your country’s economic and political situation. Tips for Improving Your Quality of LifeTo improve your quality of life, it might be helpful to first assess your quality of life in different domains and focus on domains where there is the most room for improvement. As a starting point, you can begin by considering the six domains chosen by the WHO (Physical, Psychological, Level of independence, Social relationships, Environment, and Spirituality/religion/personal beliefs). Do these domains resonate with you? Do you feel that some of these domains are irrelevant to your life, or that other key domains are missing? Really dig in and ask yourself how and why you might be falling short in these areas. Below are some examples of questions, based on some of the WHO’s domains, to get you thinking. Physical

Psychological

Social Relationships

Spirituality/Religion/Personal Beliefs

The next steps you take will depend on your answers to the above questions and any other questions you come up with for yourself. Improvement in any domain will not be a quick fix or overnight change. Instead, changes will be slow and gradual and likely based on minor habit changes in your everyday life. Focus on aspects of your life that you have the power to change - there are plenty. Remember to track your progress, either by taking a quality of life assessment now and after a period of time, or by reflecting regularly in a journal. Seeing your progress can motivate you to continue your journey. In SumThe theory and research behind quality of life are wide-reaching and nebulous, but that doesn’t mean reflecting on yours is a futile endeavor. By breaking it down into domains and assessing yourself formally or informally in each domain, you can determine how best to spend your time to improve your quality of life and overall well-being. References

Learn the philosophy behind self-acceptance and discover effective ways to cultivate acceptance for yourself. Self-acceptance is an act of embracing all your attributes, whether mental or physical, and positive or negative, exactly as they are (Morgado, Campana, & Tavares, 2014). From time to time, we may struggle to accept certain qualities that we have. Whether we were criticized as children or compare ourselves to what we see in popular culture or on social media, it is not always easy to find ways to extend compassion to ourselves. Nevertheless, accepting who we are remains vital for our happiness and overall well-being. Self-acceptance is necessary for our psychological health and overall well-being. Read below for a more in-depth explanation of each of these facets. Self-Acceptance to Psychological HealthLow self-acceptance can be one way that our psychological health suffers. When we don’t fully accept ourselves, we put ourselves at a higher risk for experiencing symptoms of anxiety and depression (Macinnes, 2006). In particular, when we reject negative qualities about ourselves, it can lead us to ruminate about these attributes, which can encourage negative self-talk. Examples of negative self-talk may include statements such as:

Negative statements that we tell ourselves can thus evolve into feelings of hopelessness, worthlessness, sadness, and anxiety. However, when we do accept ourselves, especially the qualities that we are not always proud of, we have more control over our emotions. In other words, self-acceptance can prevent anxiety and depression. Self-Acceptance for Happiness and Well-BeingLike psychological health, self-acceptance is a key to our happiness and overall well-being. When we have more control over our thought patterns and feelings, we can manage negative self-talk better, too. In fact, higher levels of self-acceptance boost our self-esteem, allow us to be more confident about ourselves, and give us the power to handle criticism better (Szentagatoi & David, 2013). Self-Acceptance as a Means for ChangePerhaps you’ve read this far and may have the impression that self-acceptance means staying stagnant or being complacent. This is easy to think about, especially because the philosophy of self-acceptance encourages us to embrace every part of ourselves. However, self-acceptance lets us recognize and wholeheartedly embrace our weaknesses so that we become aware of the things in our lives we do want to change. Personal growth is amplified through a lens of self-acceptance. We cannot improve ourselves without being in touch with who we are. In turn, becoming more self-accepting lets us practice more acts of self-love and self-compassion, which help us transform into our most authentic selves (Boyraz & Kuhl, 2015). How to Practice Self-AcceptanceThe theory behind self-acceptance sounds great, but how do we begin to practice this in our daily lives? Let's look at a few techniques you can try. Remind yourself that you are a work in progress.Have you ever started a new hobby? Perhaps you’ve been wanting to expand your skills in the kitchen and start taking a baking class. You notice your classmates make a delicious batch of chocolate chip cookies, but you accidentally burned yours in the oven. When you make mistakes, negative self-talk may be peeking around the corner, ready to break into your mind. Maybe you tell yourself, “I’m a horrible baker” or “I’m never coming back to class because I’m not good at this.” An alternative to this cognitive response is to tell yourself you are a work in progress. Next time you find yourself in a new situation that you are not automatically good at, try saying, “I will get better at this”, or “It’s okay, this was my first time, and mistakes happen.” Allowing yourself to accept that you messed up this batch of cookies can release the expectation of perfection and enable you to happily try again (Carson & Langer, 2006). Keep a gratitude journal.If you catch yourself thinking about things that went wrong during the day or ruminating on what your negative qualities are, you may want to think about ways to shift your focus to a more positive mindset. One way to accomplish this is by having a journal (or maybe even the notes app on your phone) to write down a few things you are grateful to have in your life every day. When we focus on the positive, we begin to reduce feelings of lack and negativity, which can boost our ability to accept ourselves more mindfully (Carson & Langer, 2006). View your experiences from a different perspective.Find yourself ruminating on a situation that evokes discomfort or unhappiness? Try looking at the situation from a different perspective or try to find a silver lining. Maybe you are headed to a party on a hot summer night, and suddenly the sprinklers come on and get your clothes wet. What a frustrating experience, right? What could you do to make it less frustrating? Maybe you laugh at the situation or find the positive (e.g., it was a hot day, and the water did cool me down). Or perhaps you talk to a loved one for their perspective on the matter. Sometimes we can remain stuck in our feelings. When we look at situations with fresh eyes, we can find things we didn’t notice before that may help us accept the experience (Carson & Langer, 2006). In SumSelf-acceptance is not a practice that we can master in a day, and that is completely okay. The important thing is to familiarize yourself with the concept and slowly find ways to incorporate self-acceptance into your own life to better support your psychological well-being and promote happiness. References

Find out what false positivity is, explore everyday examples of false positivity, and learn how you can avoid it. False positivity is the positive attitude we force into situations where positivity is not called for. If this doesn’t sound awkward to you, the following analogy may help you see that it is. Assume positivity is akin to sugar – it is sweet and enhances the flavors of some bland foods, making them taste more appealing. We all love happiness and positive attitudes, thoughts, and feelings (Ford & Mauss, 2014), just the way we love the sweetness of sugar. Hence, added sweetness to bland foods is similar to how a positive attitude can help us deal with mundane tasks and everyday hurdles. However, some foods just don’t go well with sugar. Indeed, adding sugar to those foods may cause them to taste awful. Instead, these foods may need a pinch of salt, a spoon of vinegar, or some other seasoning to become more palatable. Therefore, just as we shouldn’t reach for the sugar jar to season every dish we are served, we shouldn’t sugarcoat every negative experience life puts on our plates. Instead, we’re better served by choosing the most appropriate reaction. False positivity can come about in two ways: either other people give our experiences a positive spin, or we do it to ourselves. But how do other people bring false positivity into our emotional experiences? It usually starts with rosy pictures or optimistic comments about an upsetting situation. Yet, these positive efforts of others can create social pressure and a denial of our true emotions. Below are some examples illustrating how false positivity can be dismissive toward our feelings and emotional experiences. In some cases, false positivity keeps us in the same situation that caused our initial reaction.

How to Avoid False PositivityNow that we understand what false positivity is and how it manifests in our lives, we can take steps to prevent it. Here are a few suggestions to help you avoid false positivity. Accept your emotions even if they are negative.Life can’t always be joyful. Inevitably, we all experience times of distress or hardship. Accepting our emotions allows us to learn how to deal with these situations. This acceptance can provide us with beneficial changes in our lives and make us more emotionally resilient in the long run. Ground yourself in facts and avoid positive spins. When faced with an adverse situation, ignoring the core problem, or giving it a positive spin doesn’t solve it. In fact, it might even make the situation worse by avoiding its causes. For instance, telling someone who lost their job that “everything will be okay in the end” or “that job was unfulfilling anyway” doesn’t solve their immediate problem, which is to be able to afford their basic needs, or their emotional needs, which are to feel supported. Nor does false positivity delve into the reason for this loss, addressing which can help them find a job or minimally understand why they might have difficulties getting hired. Don’t judge others’ feelings. Unless we avoid all human contact, we can’t run away from observing others suffer or when they try to talk to us about their emotions. If someone is telling you about something upsetting, try to be empathetic. Even if you were to react differently in the same situation, judging or dismissing their negative emotional reactions won’t benefit anyone. In most cases, people tell you about these situations because they trust you, and they need someone to listen and validate their experiences to help them make sense of their situation and heal. Seek proper support.If we are dealing with negative emotions, it helps us heal to talk about how we feel. Yet, we might need to be selective about who we are opening up to. Sometimes the people closest to us don’t have the emotional maturity or empathy to understand what we are going through. If that’s the case, you might consider talking to a therapist or joining a support group to share your experiences with others in similar situations. Provide solid support.When a friend or a loved one tells us about a problem, most of us utter words of support without even thinking about whether we are actually supportive. That’s why many of us believe we are helping them when we say phrases like “everything will be fine” or “it could be much worse.” So how can we support them without invalidating their emotions and experiences? Here are a few examples you might try:

In SumSometimes, false positivity may be hard to recognize as it typically hides within well-meaning comments and encouragements. We can avoid false positivity by learning to recognize its signs and developing strategies to respond to difficult circumstances more authentically. References

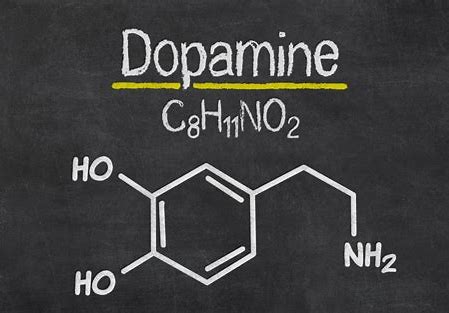

Learn more about dopamine, serotonin, oxytocin, and endorphins, and discover natural ways to boost them. Before talking about happiness hormones, it is important to understand what hormones are and how they are produced. The endocrine system works together with the nervous system to influence many aspects of human behavior. Hormones are chemicals produced by different glands in your body. They are chemical messengers and travel through the bloodstream to tissues or organs (National Cancer Institute). Hormones work slowly and over time, impacting many different processes such as:

When you do things that make you feel good, such as connecting with a friend or eating ice cream, your brain is releasing what scientists call “happy hormones.” These hormones got their nickname because of the positive feelings they produce. These “happy hormones” are:

These feel-good hormones promote happiness, pleasure, and positive emotions. The cool thing about these happiness hormones is that you have a say when they are released. Whether you have a good laugh with your friend or do some exercise, your brain is releasing these feel-good hormones. How to Boost Happiness HormonesDopamine

Serotonin

Oxytocin

Endorphins

In SumHappiness hormones—dopamine, serotonin, oxytocin, and endorphins—are essential for your well-being. You may increase the levels of these hormones without any medication by making simple changes in your lifestyle, such as exercise, diet, and meditation. In the end, these things can make a big impact. References